Opinion: Funding The District

An analysis of two common arguments

Periodically over the past few years, the BOE goes to the community for increased funding through various means. When this happens, the same debate appears on social media, no matter the need, no matter the amount of the ask. One camp cries, “Our taxes are already too high! Cut spending!”, while the other cries, “More money equals better education!”. Both statements are made regardless or how responsible, or how ridiculous, the ask is. So how can we sort out the truth? To do this, perspective is needed.

Lenawee County has one of the highest median property taxes in the United States, and is ranked 479th of the 3143 counties in order of median property taxes. The average yearly property tax paid by Lenawee County residents amounts to about 3.42% of their yearly income. There are many different taxes that make up the entire tax burden of any municipality, however. Michigan happens to rely heavily on property tax to fund education.

Proposal A, an amendment passed in the Michigan legislature in 1994, increased sales tax rates and decreased the annual property tax. This amendment also shifted more financial responsibility for public education from the state to local counties. The Headlee Amendment in 1978 mandates that if property assessments grow faster than inflation, property tax revenues must be rolled back so that the total revenue growth does not exceed the inflation rate. In spite of good intentions, this amendment can result in higher taxes to offset increased expenses during inflationary periods.

While it is fair to say that taxes are high here in Tecumseh, the assertion “too high” is subjective. “Taxes are too high for me” may be a more honest assertion, as it depends on the return on investment for each resident. The takeaway here is that, even with significant tax revenue, our school district can still fail to cover expenses. If you’d like to know more about indicators of district funding (expense/funding ratio), be sure to check out my upcoming article on fund equity.

The other argument made is that more money equals better education. While this is true some of the time, it is not true all of the time. The Law of Diminishing Returns states that profits or benefits gained from something will represent a proportionally smaller gain as more money or energy is invested in it. We would likely all agree that this district could not survive on a budget of $50,000 total. In this case, another $5,000 would surely increase academic outcomes. What if our funding was $5,000,000,000? Would an additional $5k on top of $5b result in better outcomes? This is unlikely.

So how do we know where that point of diminishing returns lies? It’s not an easy task to determine, as there are so many factors that contribute to academic success outside of funding. Studies have shown, however, that some investments are worth more than others. As a general rule, targeted investments are more valuable than across-the-board funding increases. Our recent sinking fund was a targeted fund increase, as it went straight to building repair. Paying up front keeps added costs (like loan interest) down.

Other targeted investments that have been shown to result in better academic outcomes are those that lower student:teacher ratio (Paul et al., 2021), fund extracurricular programs such as orchestra (King, 2016), provide assessment and feedback systems (Ahmed et al, 2021), provide counseling and social services (Mulhern, 2020), and those that provide evidence-based curriculum (such as project-based learning) that cater to modern skills and critical thinking (Ergül & Kargın, 2014).

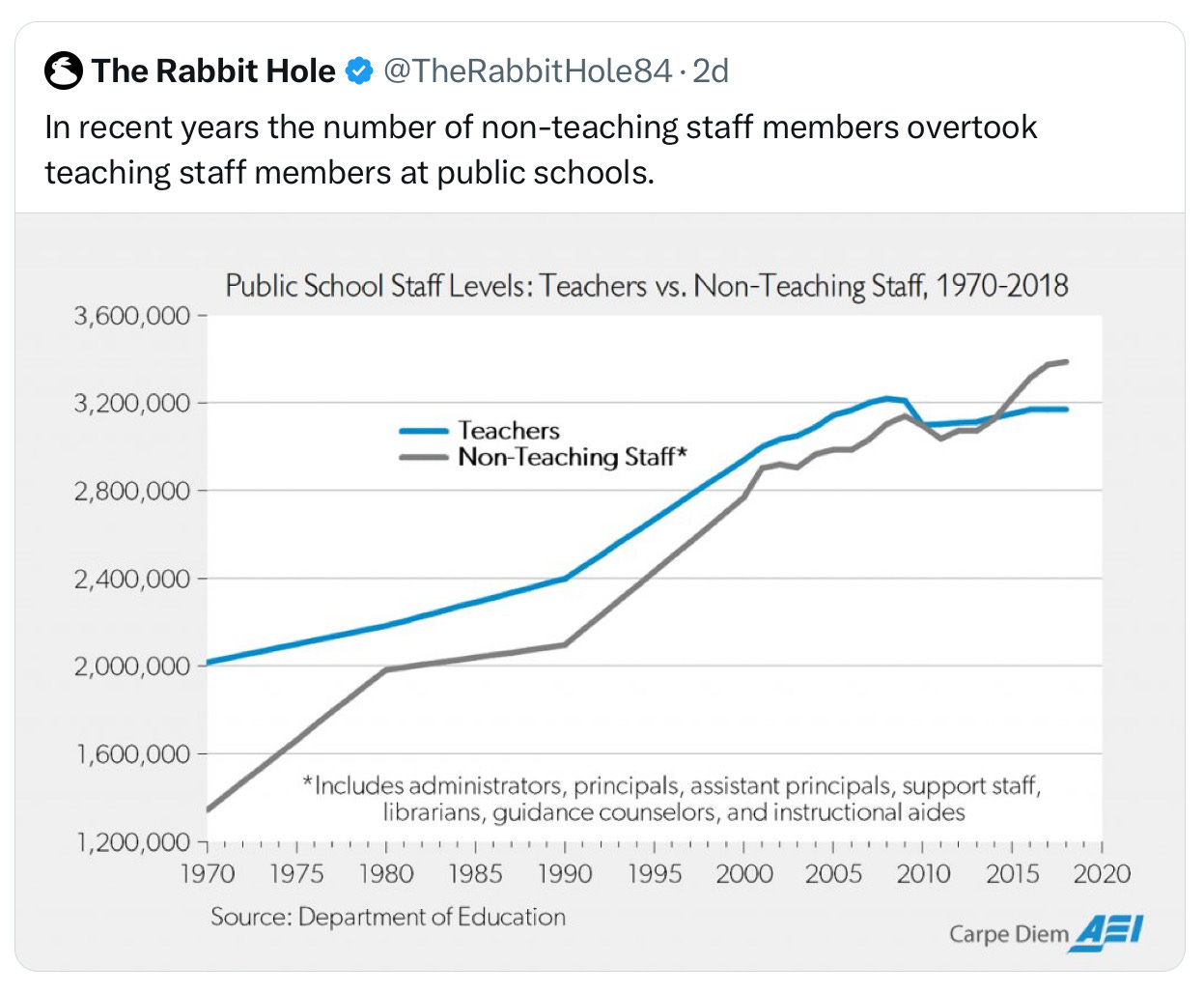

Funds that are primarily directed towards administrative overhead rather than educational resources, teacher salaries, or direct student support may not have a corresponding rise in educational quality. Some on social media have highlighted concerns that much of the increased funding in our education system goes to expanding administrative costs rather than enhancing classroom learning. While this may be less of a concern in a district as small as TPS, it still defies that narrative that all education spending is inherently “good”.

Education outcomes are also influenced by numerous factors beyond just funding, such as teacher quality, student socioeconomic background, parental involvement, and community support. In some cases, the educational system might be resistant to change due to entrenched bureaucratic practices or cultural norms. If the district is not receptive to innovation or reform, additional funding might not lead to substantial improvements.

While there isn't a universally applicable "point" of diminishing returns for all districts due to their unique circumstances, some general observations can be made:

Lower Funding Levels: At lower funding levels, additional resources can have a substantial impact on educational outcomes, particularly in underfunded districts.

Higher Funding Levels: Once a certain threshold of funding is reached, the benefits of further increases diminish unless they are strategically allocated. This threshold might vary, but it often involves ensuring basic resources, qualified teachers, and support systems are in place before additional funding yields less significant returns.

Quality Over Quantity: The quality and efficiency of how funds are spent become increasingly important. Districts might reach a point where more money does not automatically equate to better education if not managed well.

In conclusion, the point of diminishing returns for district education funding is not a fixed number but a dynamic point influenced by how well funding is aligned with educational needs and efficiently utilized. A district can still be underfunded even if taxes are high. Academic success can still flatline in spite of increased funding. Neither argument can be used for every situation, so it’s important to do the research for each funding proposal and vote according to merit, not mantra.

References

Ahmed, M., Thomas, M., & Farooq, R. (2021). The impact of teacher feedback on students’ academic performance: A mediating role of self-efficacy. Journal of Development and Social Sciences, 2(3), 464-480.

Ergül, N. R., & Kargın, E. K. (2014). The effect of project based learning on students’ science success. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 136, 537-541.

King, M. E. (2016). Comparing the effects of elementary music and visual arts lessons on standardized mathematics test scores. Liberty University.

Mulhern, C. (2020). Beyond teachers: Estimating individual guidance counselors’ effects on educational attainment. Unpublished Manuscript, RAND Corporation.

Paul, S. C., Islam, M. R., & Hossain, S. (2021). The Impact of Student-Teacher Ratio on Literacy Rate of Bangladesh: A Study on 64 Districts of Bangladesh. Journal of Business Analytics and Data Visualization, 2(1), 1-6.